The Island Means Minago by Milton Acorn

Winner of the 1975 Governor General’s Award for Poetry or Drama

When someone thinks of PEI literature, the first image to pop into their mind would be that of Lucy Maud Montgomery and her little redhead Anne. I’ve written on this blog many times before about the development and current state of PEI literature and how the last 25 years has really been a high point for writing in the province. There was very little early (pre-1950s) PEI literature worth discussing. Lucy Maud really was the grandmother of PEI writing and her contemporary Sir Andrew Macphail was the grandfather with his masterpiece The Master’s Wife. But, PEI lit as we know it now was really founded in earnest with Milton Acorn’s 1956 self-published mimeographed chapbook In Love and Anger. Acorn was a very different voice from his contemporaries; he was a working man’s poet. A World War II veteran with little formal education, The People’s Poet spent most of his life living off a Veteran’s Affairs pension due to war injuries. Some of his titles were best-sellers in Canada and he was a superstar in the world of poetry – even marrying Gwendolyn MacEwen for a short time. The 1975 collection The Island Means Minago, his only collection to win the Governor General’s Award, is Acorn’s most ambitions treatise on his home province and contains many of his signature poems.

The Island Means Minago is a very cohesive volume, both in terms of narrative and themes. It mixes narrative poems, lyrics, prose pieces, dramatic scenes, and photos to tell the story of his people. Right in the opening poem, Acorn’s love of his island is evident:

In the fanged jaws of the Gulf,

a red tongue.

Indians say a musical God

took up his brush and painted it,

named it in His own language

“The Island”.

In terms of narrative, Acorn takes on a number of issues prominent in Island history (honestly, if you’re familiar with these items it makes this a much more enjoyable book): the absentee landlord problem from the 19th century and Island Development Plan that began in the 1960s that would be top of mind in 1975. Acorn uses these narratives to tie together the thematic concept of this book. It is no secret that he was a far-left socialist, and that is the lens through which the author writes. He lambastes capitalism, roasts the ineffective administration of the government for not representing the people, and takes up the cause of the proletariat.

As I mentioned, Acorn was the working man’s poet. He was a big personality and it is easy to envision him reciting these poems in a pub throwing back beers and shots of whiskey. His language is accessible and free of those 20-dollar-words too often used by MFA graduates. But, that is not to say that these poems are “simple,” quite the opposite. Acorn manipulates genre and form in fascinating ways, he often uses an isolated rhyme as a narrative turning point, he creates intriguing imagery while using down-home dialect, and he is very cognizant of the sound, the music so to speak, of his poetry by doing interesting things with repetition, dialogue, and syllable structure.

An element of this book that was interesting was the collection of prose pieces. Each of the three sections has one prose piece, with each being about 10 pages in length. It is hard to classify these parts – as I said, he does interesting things with genre. These three pieces are not prose poems, but they’re not exactly stories either. They’re something of a blend of history, storytelling, social commentary, and political treatise. These prose pieces were excellent additions to the poems because they provide some historical and socio-economic context and further entrench Acorn’s socialist themes.

Finally, the actual physical volume itself is an interesting specimen. It was published by NC Press, who according to the ads in the back of the book, published the paper New Canada, that reported “on the struggles being waged across the country for independence and socialism” and was also the leading publisher of books and documents from the People’s Republic of China. So, the strong leftist overtones shouldn’t be surprising.

I’ve said before that PEI has the most nationalistic literature and sense of identity in general in English Canada. This collection was one the flashpoints for this Island literary tradition. The Island Means Minago is a great example of Maritime and PEI poetry, an excellent collection of historical poetry, an interesting political exposition, and just an overall engaging read.

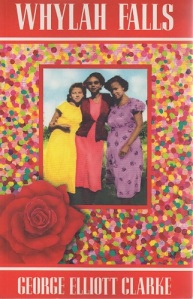

Whylah Falls by George Elliott Clarke

Winner of the 1991 Archibald Lampman Award

Selected for Canada Reads 2002

I’ve written on this site before about my love of George Elliott Clarke. He is a master writer, a brilliant public reader and speaker, a top notch literary scholar, a genuine nice guy, and Toronto’s Poet Laureate. His writing is a mix of down-home Nova Scotia charm and rich African-Canadian historicism – which he dubbed “Africadian”. Whylah Falls is Clarke’s second book and one of signature works. This volume is the narrative of the residents of the fictional Nova Scotia black village of Whylah Falls, focusing primarily a young lady named Shelley and her immediate family. This book has the notable distinction of being selected for the first edition of Canada Reads held back in 2002 (defended by sci-fi author Nalo Hopkinson, finishing second only to the winning title In the Skin of a Lion) and still remains one of only two books of poetry to be featured on the competition.

Whylah Falls is a book of poetry but it is a mixed-genre book; it uses traditional narrative poems, prose poems, sermons, dramatic monologues, theatrical scenes, newspaper-style articles, letters, and photography. This collection is often referred to as a novel told through poetry, but I think a better description is a cycle of stories told through poetic forms as each section focuses on different groups of characters in the village.

This has become an important and landmark book in Canadian literature and is now solidly in the canon of Black Canadian writing. I read a selection of these poems in a Canadian Lit course at Saint Mary’s University in 2003 but I had never read the whole volume from start to finish despite the fact I’ve had a first edition sitting on my shelf for years (oddly enough the first edition cover is really terrible and both the 10th and 20th anniversary editions are much nicer). I really really wanted to love this book. I recently re-listened to Canada Reads 2002 and Hopkinson’s impassioned defense ignited a desire to immerse myself into Clarke’s best known world. But. But, in the end, I wasn’t blown away like I was hoping I would be. To this reader, Whylah Falls was just ok. And here’s why.

Firstly, I absolutely adored the love poetry in the two sections titled “The Adoration of Shelley” and I loved the whole section “The Martyrdom of Othello Clemence.” The imagery in the love poems was beautiful, sensual, and tastefully erotic and the narrative in “The Martyrdom” was powerful and vivid. Overall though, I was a little underwhelmed by a lot of the book. I think the primary problem was the huge cast of characters; I was continually lost and had to keep referring back to the Dramatis Personae. Unlike a novel or a play where there is ample narrative introduction and development of primary characters, this format didn’t really allow for that, so you are simply thrown into the middle of this dynamic little town (almost the identical problem I had with Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town).

I want to be clear that my rating of “just ok” doesn’t mean that I didn’t like the book. The quality of writing was very high and the innovative nature of the volume was superb. Ultimately though, Whylah Falls didn’t grab me the way Execution Poems did. Maybe I was just the wrong audience or I read the book at the wrong time. All that being said though, this is still one of the most important books in contemporary Canadian literature and maintains an important place in African Canadian culture.

Night Work: The Sawchuk Poems by Randall Maggs

Winner of the 2008 Winterset Award

Winner of the 2009 E.J. Pratt Poetry Prize

Winner of the 2010 Kobzar Literary Award

Shortlisted for the 2009 Heritage and History Book Award

Longlisted for the 2009 Relit Award for Poetry

A Globe and Mail Best Book ~ 2008

I need to start this review off by prefacing it with the confession that I am not a hockey fan; it is not that I dislike hockey, I am just not a follower and really know very little about it. So, that being said, I was surprised how interested and excited I was to read Night Work and I was even more amazed by how much I enjoyed it. Even being the hockey ignoramus that I am I still had somewhat of an idea of who Terry Sawchuk was and his stature in the sport. This collection joins a Canadian tradition of poetic historical revision; Randall Maggs has taken a historical figure and molded this person into one of the great literary characters of the last 20 years, much the same way Michael Ondaatje transformed Billy the Kid decades ago. This book is a masterpiece. Period.

The star hockey player in our contemporary setting has a bit of the rock star personae. Maggs closely examines what life was like day-in and day-out for these gritty workhorses; the title says it all, Night Work. Sawchuk’s life as portrayed in this book felt like an unrealistic marathon. The punishment both physically and psychologically that hockey professionals of this generation took is just mind boggling. One scene in particular that I loved was when Sawchuk’s coach was arguing with him about how detrimental goaltenders wearing masks would be. Most of the poems in this collection are told from “characters” with personal and intimate knowledge of Sawchuk, as opposed to being told from Sawchuk’s; I really like this technique, it helps maintain that sense of the goalie being an unknowable legend, it keeps that sense of detachment yet provides insight into the man in an almost intense fashion.

This collection of poetry read like a novel. There were very defined characters and they developed in much the same way they would be in a great piece of fiction. I also felt there was a very defined story arc as well. The poems were all highly narrative and detailed in the style of Al Purdy. Through Maggs’ examination of Terry Sawchuk we also get something else, Night Work is a chronicle of hockey in general during this period, its role in the public consciousness, and ultimately its importance in the culture of Canada and the northern US.

Supplemented by beautiful original photography of Sawchuk’s time and prefaced by an excerpt from his autopsy report, Randall Maggs has truly captured one great man’s short life in this fitting poetic tribute. Night Work is still one of the most recognizable books of poetry on the shelves of Canadian book stores two years after initial publication. This book is complex, detailed, beautiful, well researched, and a must read for all Canadians. Below is a short clip of a game from the 1964 Stanley Cup finals where Sawchuk played goal for Detroit so you can see a tiny bit of his on-ice genius.

Execution Poems by George Elliott Clarke

Winner of the 2001 Governor-General’s Award for Poetry

I have had the pleasure of seeing George Elliott Clarke read his poetry on several occasions; the first time in 2002 at a presentation he did for a Canadian poetry class I was taking at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax. Clarke is definitely one of the most entertaining readers I have seen. He does more than just read, he performs, he puts his heart and soul into the presentation of his work. In his 2001 collection, Execution Poems, this passion leaps off the page. In this short book, only around 30 pages of writing, Clarke tells the story of brothers George and Rufus Hamilton, who were actually Clarke’s cousins, who killed a taxi driver in Fredericton in 1949 and were hanged for their crime only a few months later. This book has been on my “to buy/read” list for a long time so when I finally ordered it a few months ago I was very excited. The street I grew up on, Hamilton Street, is actually named after the Hamilton family of which George and Rufus were a part of. Clarke in this small collection looks at racism, desperation, and examines whether things really have changed almost a half-century since the hanging.

This book has a strong narrative arc with most of the poems told from the point-of-view of either George, Rufus (or Rue), or both. The writing is done in a conversational tone which greatly enhances the desperation of the characters circumstances. The central pair seems to be fairly well-education, or at least well read, in comparison to their socio-economic contemporaries. The author sets a scene of fear for the pair: beginning with a fear of starvation and eventually ending with fear of the consequences of their actions. The poem “The Killing” is my favorite in this collection, and I think this is actually one of Clarke’s best poems in his entire library. Clarke has the power to paint a vivid picture and expose a man’s deepest feelings with only a few words. Here is a power example from this poem:

Rue: Here’s how I justify my error:

The blow that slew Silver came from two centuries back.

It took that much time and agony to turn a white man’s whip

into a black man’s hammer.

Geo: No, we needed money,

so you hit the So-and-So,

only much too hard.

Now what?

Rue: So what?

In nine lines Clarke manages to embody generations of the African-Canadian experience.

The actual book is work of art as well. Published by Gaspereau Press, publishers of this year’s Giller winner The Sentimentalists, this paperback has thick paper with a pronounced grain, a dust jacket, and the paper blocks are sewn as well as glued, you can tell that a lot of love went into making these volumes. In 2005 George Elliott Clarke released a novelization of this story entitled George & Rue; this novel was released to much popular and critical acclaim, being nominated for several prestigious awards. For anyone interested in the African Canadian experience of Atlantic Canada, or as Clarke has dubbed them, Africadians (combination of African and Acadian), then this book, along with his best known collection, Whylah Falls, should be on top of your list.