Dance on the Earth by Margaret Laurence

I’ve said before on this blog that Margaret Laurence is my number 1 favorite author. It is because of her I fell in love with Canadian Literature and reading in general. Laurence died relatively young and had very little output after her magnum-opus, The Diviners, was published. Over the years, I kept a few of Laurence’s works on reserve for future reading because I don’t like the finality of reading everything she has published. He last book, and only major work after The Diviners, is her posthumously published 1989 memoir Dance on the Earth. Laurence died in 1987, shortly after completing a semi-final draft and before publication. In the foreword, her daughter Jocelyn does an excellent job of describing the last few months of Laurence’s life and the rush and struggle to finish this book. Her cause of death wasn’t actually revealed until James King’s biography was published many years later. There is no particular reason why I decided to read this now, I just felt that it was time. Dance on the Earth was an excellent coda on the writing career of a masterful author. In fact, this strong woman being ripped from this world while writing her memoirs could even be described as Laurence-esque.

Laurence crafts an autobiography that is all her own. She doesn’t follow a standard A-to-B-to-C structure. Instead, she frames each of the four primary chapters in terms of the important mothers in her life: her biological mother, her step-mother, her mother-in-law, and finally herself. Within each of these frames, Laurence discusses the major events, important people, and central places that made her who she was and helped shape her pacifist and feminist views. Interestingly, she doesn’t really get into discussing her own writing until the chapter where she focuses on herself. Laurence gets into her state-of-mind with her works, her reactions of reviewers, her dislike of the publicity/business end of it, and why The Diviners was her last major work. This section more than the rest is really a fascinating glimpse into a brilliant creative mind. Additionally, the memoir is peppered with wonderful letters between Laurence and others, with the letters to Adele Wiseman being a definite highlight.

The main bulk of the book is written with the same understated powerful prose that punctuated her Manawaka cycle, except Laurence herself takes the place of Hagar, Rachael, Stacey, Vanessa, and Morag. She is very open, vulnerable, and pulls no punches. My one negative critique of the book is some of the items included in the “Afterwords” section. The previously published essays, including articles on nuclear disarmament, feminism, and a convocation address were fantastic, they were wonderfully written, articulate, and quite persuasive in their arguments. But, the poems that were included were not that great. It upsets me a little bit that the final work of Laurence’s career is concluded with a bit of mediocre poetry that seems to have been written for personal occasions, not publication. I’m sure this was an editorial decision made after Laurence had left us.

It’s clear that Margaret Laurence knew her life was coming to an end (as we now know she made the decision herself on when it would end). This was also clear in the way the memoir ended. She seemed to wrap things up quickly and almost suddenly because she knew that’s how it had to be. This is not a criticism of the book or even something that takes away from it. Instead it further punctuates that the fact that this great author had a lot more to give to our country, even if her prime writing days were behind her.

The Door is Open by Bart Campbell

Finalist for the 2002 Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize

Finalist for the 2002 City of Vancouver Book Prize

Golf season is winding down so I guess it’s time to start reviewing some books again. I recently moved my bookshelves around and I wanted to read a book from the top shelf of the first case, which happens to be my paperback non-fiction shelf. The book that caught my eye was Bart Campbell’s The Door is Open: Memoir of a Soup Kitchen Volunteer.

This memoir tells the story of a hospital lab technician who volunteers at a drop in centre in Vancouver’s East Hastings area after he and his wife separate. Across Canada, East Hastings has the reputation of being a very poor, hard, and drug and crime infested area. Images are conjured up of prostitutes, heroin, and destitution. This memoir was published in 2001 so it was before the opening of the safe-injection site InSite, and other focused government efforts, started to make a very small dent in the visible poverty.

This book is very short, with the epilogue it clocks in at only 144 pages, but it is 144 very well used pages. Each of the 10 short chapters pack a very strong punch. The Door is Open is more than simply a memoir filled with anecdotes about the characters he came across while volunteering, of which there are lots; Campbell looks at the nature of poverty and all of the complications that go along with it. In methodical fashion, he explores concepts of poverty and homelessness, crime, addiction, prostitution, mental health and suicide, and survival. Campbell beautifully pieces together cold-hard facts, personal observations, anecdotes, and expert opinions to paint a brutally honest portrait of East Hastings, which is, as he points out, the “poorest forward sortation area of all 7,000 postal prefixes” in Canada.

At the end of each chapter, Campbell has a coda of sorts with excepts from diaries he kept while volunteering. These excerpts act as real human examples of the themes he explored in the preceding pages. Also peppered throughout the book are beautiful black and white photographs of the East Hastings landscape.

I’ve been fortunate in my life that I’ve never had to stare down the prospect of real poverty. When I was younger I was the stereotypical “poor student,” but this was far from being “poor.” It just meant I had to call my parents to borrow a few bucks. I always had a job, a roof over my head, cable TV and internet, food, a car, and a few books to read. Poverty and desperation on this level is something middle-class Canadians like myself just don’t have to think about, even though, as Campbell mentions, Statistics Canada points out that most Canadians are only a few months away from homelessness. The Door is Open is a hard read because it forces you to face this world. The author pulls no punches and maybe, just maybe, he might change a few minds on the homeless.

Canada is in the midst of a federal election and we recently had a provincial election here in PEI. As I finished this book last night, it actually got me thinking (which was likely a goal Bart Campbell had), about the political approaches that are the typical go-to’s in this country. Over the last few years, it’s been all “affordable housing.” Just last week Liberal leader Justin Trudeau promised tax credits to developers to build low income housing. If Trudeau came to my door step right now, I would hand him a copy of this book, and ask him how this would help the people Campbell writes about (answer is, it wouldn’t).

The Door is Open was on the longlist for Canada Reads this year; I hadn’t actually heard of the book prior to this. Even though it is almost 15 years old at this point, it is still, quite sadly, very relevant. In a country with an economy worth over $2,000,000,000,000, there is no need for people to have such a meager existence. This is a fantastic book and a must read

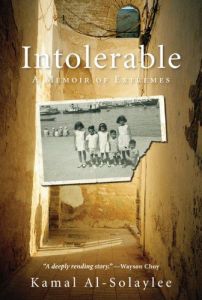

Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes by Kamal Al-Solaylee

Selected for Canada Reads 2015

Winner of the 2013 Toronto Book Award

Shortlisted for the 2012 Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction

I don’t read a lot of memoirs. It’s not that I have something against the genre, I have at least 10 on my to-read list, I just never seem to pick many up. This year’s Canada Reads included a memoir by journalist and professor Kamal Al-Solaylee – Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes. This books charts his development as a gay man in the Middle-East and his eventual relocation to his adopted home of Toronto. This short memoir is so much more than an individual man’s coming-out narrative. Intolerable is a thought-provoking blend of personal memoir, family dynamics, history, economics, and political science. Ultimately, this is the story of Kamal Al-Solaylee, but the sentiments he espouses are no doubt almost universal amongst the millions of immigrants in Canada.

What I loved about this memoir was the holistic approach Solaylee took. There are three broad topics that he tackles: his own development and coming out as a gay man, his relationship with his family, and the increasing religiosity and intolerance in the Middle East. Each of these three threads is tied into the others and seamlessly flows into every chapter.

This book really grabbed me. The author’s background as a journalist really shows in his easy to read and highly informative prose. With the perspective of a Yemini who lived in Cairo and Beirut over the course of several decades that is now solidly Canadian, the author gives a stellar account of the rise of religious intolerance in the Arab world and succinctly gets down to the root causes as he experienced them. It would be surprising for a lot of readers to realize that this state of affairs in this part of the world is a relatively new thing. Solaylee discusses how when he was a kid his sisters would go bikini shopping for their summer vacation while now they must wear a niqab and be accompanied by a man. He gets into the root economic causes that spurned this social change and even throws out some ideas about what the cures may be – including some thoughts on the Arab Spring.

Ultimately though, this is a story of family. Solaylee has a relationship with his family that is complicated beyond what any native born Canadian could really comprehend. The youngest of over 10 kids, and the son of an illiterate lower class mother and former business tycoon father, Solaylee could tell from an early age he was different from his siblings – and this feeling only got stronger as time went on. As more and more distance was between him and them, and the situation in the Middle East deteriorated, things became even more complicated. And as his cosmopolitanism grew, his unhappiness with their situation increased.

So looking through the lens of this year’s Canada Reads theme, “One Book to Break Barriers,” this book shatters a lot of them. Solaylee’s memoir explores homosexuality in the Third World, the nature of Islamic intolerance in the Arab world, post-colonialism and its lingering effects, multiculturalism and its downfalls, and the immigrant experience. This eye opening memoir is informative, but not dry. It takes points-of-view on issues but doesn’t sound preachy. And, near the end of the book, it is a deeply moving love-letter to Toronto.

Intolerable is one of the best memoirs I have ever experienced. The problem I sometimes run into with this type of writing is that it is so self-centered and devoid of context that as you read you continually ask “why should I care.” Kamal Al-Solaylee is now, without any disrespect intended, a relatively average urban Canadian. He was a journalist for numerous publications after paying his dues and working his way up, and he is now a journalism professor. But, the story of how he got there is fascinating, because it is not simply his story, it is the story of him, a family, and very volatile region. I still have 3 Canada Reads picks to read, but I’m thinking this book may be hard to top.

What Really Happened is This by Dianne Hicks Morrow

Winner of the 2012 PEI Book Award for Poetry

I was initially introduced to this book in my Contemporary PEI Literature course when we read a selection of five poems. What Really Happened is This is the award winning poetry memoir, and second collection of poems, by PEI writer Dianne Hicks Morrow. I was greatly intrigued by the idea of a poetry memoir and didn’t know what to expect. These poems were, for the most part, very sad; but, I do not mean that in a negative way. Instead, I mean that Morrow has opened herself up in an incredibly close and intimate way and is bearing her soul to the world during a very personal and traumatic part of life. Being a “memoir”, one cannot separate “poet” and “speaker” – the result was a heightened emotional connection with the writing.

The poems “Belonging” and “What Really Happened Is This” get to the core of what Morrow is trying to do. Both poems are very personal and easily to take to heart. “Belonging,” a look back at Morrow’s feeling of fitting in and the difficulties that that can entail in Prince Edward Island, is very reflective and introspective. She looks back the little things that helped shape her, contemplates being an “Islander,” reflecting on the minutiae of human existence. And ultimately, as I’m sure happens with most people, trying to figure out where one “belongs” simply leaves more questions.

The title poem, “What Really Happened Is This,” is a longer multipart poem and it is by far the highpoint of Morrow’s collection. It is absolutely heart-wrenching and will leave you pondering long after you’ve finished the book. It juxtaposes two powerful images that most people with severely ill loved ones probably go through: the person that you grew up with and love and the person who is connected to machines, surrounded by doctors, and away from home praying that they can return to who they used to be. The whole collection, but this poem in particular, really draws the line from personal tragedy to memory to reality and back again.

I had the opportunity to spend a couple of hours with Mrs. Morrow and discuss her writing. She is very passionate about poetry and PEI writing. Her reading from this book really added a depth to the personal character of the poems. Every poem in this 73 page collection is a work of art – with the two I discussed above being the highlights. They physical book itself, published by PEI’s Acorn Press, is quite attractive and would look great on any bookshelf. What Really Happened is This is a quick, touching, accessible, and memorable read.

The Boy in the Moon by Ian Brown

Winner of the 2010 Trillium Award

Winner of the 2010 B.C. National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction

Winner of the 2010 Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction

Finalist for the 2010 Governor-General’s Award for Non-Fiction

A Globe and Mail Best Book – 2009

A Coast Best Book – 2009

An eye Weekly Favorite Book – 2009

As a journalist for The Globe and Mail, Ian Brown has built a reputation for bitingly honest and in-depth reporting. The Boy in the Moon is his memoir on raising his disabled son and the circumstances that surround it and come from it. This is not the usual type of book I read but my expectations were very high when I picked up this memoir; it had beaten out Anne Michaels, Alice Munro, and Margaret Atwood for the 2010 Trillium Prize, no small feat. My expectations were not only met but were greatly exceeded. Brown weaves an incredible roller coaster of a narrative about his son Walker with a great coherency that is so often absent from a memoir. The Boy in the Moon would rival any thriller or action story as a fierce page-turner.

The central figure in the book, Walker Brown, suffers from Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, often shortened to CFC; a very rare genetic disorder with roughly around 100 confirmed cases worldwide. CFC affects many aspects of a child’s life: the sufferers have physical deformities, it causes cardiac and intestinal problems, and it also causes developmental delays. One thing that is focused on very heavily in the book is just how little is known about this disorder. You will never find two CFC children who are alike and have the same disabilities. Throughout Brown’s journey we are exposed to the sometimes frightening routine of day-to-day life for a parent of a severely disabled child, how the system tends to shirk their responsibility of helping the families of those children, various support systems around the world, Walker’s eventual move into a group home, the lives of other CFC children around the continent, and the science behind the disorder.

Ian Brown’s prose are truly superior to what I am used to seeing in this type of piece. This book is written with literary yet accessible language. You are immediately absorbed into the joys and nightmares of this family’s experience. Page after page is filled with revelations that someone like myself has never really had to contemplate; whether it is the difficulty in getting a small government grant to purchase necessary medical equipment, the huge struggles to find an adequate group home, or the story behind the legendary L’Arche communities around the globe you feel what I believe the author wants you to feel. In looking through the book for a few passages to make my point I couldn’t narrow it down to one or two; every single paragraph is filled with wisdom that can only be gained through the hardships and joys that the Browns endured.

At first glance different people may make different assumptions about this memoir. In the end I look at this book as two things: first it is a tale of hope, of how this broken child, disabled because of a slight spelling mistake in the massive human genetic code, brought so much happiness to everyone around him; second this is a book about how the Canadian social system can so easily, and frequently does, fail the families of special-needs children. Great literature in my opinion should leave a lasting impression on the reader. There are only a few pieces that have that incredible ability to change the reader, change their outlook or their perspective on certain issues: “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” by Alice Munro, The Diviners by Margaret Laurence, and Let Us Compare Mythologies by Leonard Cohen were really the only literary works that I could genuinely say had this affect on me; The Boy in the Moon by Ian Brown is without a doubt now on this list.