The Colony of Unrequited Dreams by Wayne Johnston

Genre: Biographical Fiction, Political Fiction, Historical Fiction, Bildungsroman

Publication Year: 1998

Edition Read: 1999 Vintage Canada paperback edition

Major Accolades: Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Prize, 1998; Canadian Authors Association Award for Fiction, 1999; shortlisted for Giller Prize and Governor-General’s Award for Fiction, 1998; Canada Reads selection, 2003.

Newfoundland and Labrador is an interesting the province – the last to join Confederation, one of the most distinct cultures in English Canada, and one of the most remote provinces in Canada. I have family connections to the province; my grandfather was born in the early 1920s and as such was a member of that last generation of Newfoundlanders that experienced life in both an independent and confederated Newfoundland. I remember as a youngster him showing me his Newfoundland memorabilia: coins and bills from the Dominion, postage stamps, and the medals he received for serving in the Newfoundland company of the Empire forces during World War II. Even though he moved to Nova Scotia in the late ‘40s and married a New Brunswick francophone in the early ‘50s, many of the old traditions of rural pre-WWII Newfoundland survived in his home until his death in 2007. Even though it is one of the few provinces I have never visited, I have a great affinity for Newfoundland.

Joey Smallwood is a name that is synonymous with Newfoundland. He dubbed himself the “Last Father of Confederation” and once elected premier he ruled with an authoritarian streak that would make Donald Trump proud for over two decades. Whatever one may think of Smallwood, is it indisputable that you cannot understand that period of the province’s history without understanding him. With that in mind, you must give kudos to Wayne Johnston and the guts it must have taken to even contemplate the idea of writing a sweeping epic with Joey Smallwood as the main character (and narrated from his first-person point-of-view nonetheless).

Epic in its proportions, The Colony of Unrequited Dreams is one of the most satisfying books I have read in a while. It combines politics, romance, elements of the bildungsroman, and as much Newfoundland culture as you can handle. The character of Smallwood and his true-love/archenemy Sheilagh Fielding are about as well developed as characters can be in a work of fiction, and that is the true power of this book. As a reader, you spend decades with Smallwood and Fielding – you mourn their failures and celebrate their triumphs. Equally as impressive as Johnston’s character development is his ability to shift narrative point-of-view and exposition style. At regular points throughout the book, Smallwood’s narration is injected with snippets of book chapters, journal entries, and newspaper columns written by Fielding. Johnston managed to create a very distinctive first-person viewpoint in these pieces and they serve a fantastic contrasting or context setting device.

This novel was featured on Canada Reads in 2003. It was defended by Justin Trudeau, long before he got into politics; Trudeau ended voting against Colony in the final round to crown Next Episode as the winner and to this day he remains the only panelist in the 15 years of the competition to vote against his or her own book. One of the primary criticisms of the novel on that show, as well as on some other amateur reviews I’ve read, is that from a biographical standpoint, Johnston takes some severe liberties with Smallwood’s story. It is true, he does – for instance, Smallwood was not on the SS Newfoundland during the infamous sealing disaster and, from a larger perspective, Fielding was not a real person. My response is… who cares? I would refer anyone who criticizes the book on this basis to the second paragraph above: “Joey Smallwood is a name that is synonymous with Newfoundland.” While the central character of The Colony of Unrequited Dreams is Joey Smallwood, I read this book as the story of Newfoundland during the formative years of 1900-1949 first, and as a story of Joey Smallwood second.

This is a long and engrossing book that should be read slow. It needs to be savored and chewed on slowly or else you risk just pounding through the magic (although I feel this is the case with all books and am a subscriber to the school of slow reading). The Colony of Unrequited Dreams has aged very well in the twenty years since it was published.

Two Solitudes by Hugh MacLennan

Genre: Historical Fiction, Romance, Roman du Terroir

Publication Year: 1945

Edition Read: McClelland & Stewart New Canadian Library, Series Five. Afterword by Robert Kroetsch

Major Accolades: Governor-General’s Award for Fiction, 1945; Canada Reads selection 2013

Hugh MacLennan

A lot can be said about Two Solitudes by Hugh MacLennan, but no matter what one’s interpretation of the novel may be, the 1945 winner of the Governor-General’s Award is inarguably one of the most important novels in Canadian literary history and an undeniable classic. This novel was resurrected into the public consciousness with its inclusion in the 2013 Canada Reads debates, where it was the runner-up. As a dedicated student, collector, promotor, and all-around fan of Canadian literature, I am almost ashamed to admit that this is my first time reading this great book.

This is a big book, both in size and scope. It is a multigenerational coming-of-age story that spans from the end of World War I to the start of World War II against the backdrop of the identity struggles and politics of Quebec during the inter-war years. There is also a great deal of commentary on Canadian literature and many autobiographical elements weaved into the novel.

Of all the threads that could be tugged on with this novel, the one that fascinated me the most was the death of the rural parish – the urbanization of Quebec society. The first section of the book, with Athanase Tallard as the central character, is an excellent example of pre-Quiet Revolution Quebec; the clergy were almost supreme rulers of their parish, religion and language were everything, and political beliefs were absolute. As WWI wound down though, this rural way of life was changing; English people were moving in, some in the population were questioning the authority of the church, and industry is beginning to be established in the rural parishes. I would also argue that MacLennan’s novel marks the death of the traditional Quebec Roman du Terroir.

1978 Film Adaptation

The final section of the book is also rife with autobiographical details and allusions to other modernist English and American literature. Paul Tallard’s decision to write about Canada almost directly mimics MacLennan’s own development as a writer. Paul’s development as a writer also has overtones of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The ideological missives throughout the last quarter of the novel are reminiscent of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. MacLennan deftly shows that he is a writer’s writer.

What will stick with me most about Two Solitudes is that it is the story of generational change. It is cliché to say this, but this novel is just as relevant today as it ever was. Paul Tallard, born at the turn of the 20th century, came of age in the shadow World War I, entered adulthood during the Great Depression, and then finds himself by enlisting for World War II. I look at the story of people my age: I started university 3 weeks before the September 11 attacks, came into adulthood with the Afghanistan War in full swing and under the shadow the American war in Iraq, and I started my career in earnest at the height of the Great Recession. A person’s world views and ideology can’t help but be heavily influenced by such events. Past is prologue and history is cyclical; it would be hard for someone my age (mid-30s) to read this novel and not see the parallels between the treatment of Paul Tallard’s generation (the G.I. generation) by his elders and the flack my much-maligned Millennial cohort receives from the Baby Boomer generation.

Hugh MacLennan is such an important writer: five-time GG winner, author of other classics like Barometer Rising, Each Man’s Son, The Precipice, and The Watch that Ends the Night. Unfortunately, so many of his works are either out of print or in between editions (Barometer Rising for instance is transitioning from its NCL edition to a Penguin Modern Classics edition). Two Solitudes is one of those titles currently out of print, as bizarre as that is to believe. The title has been around in various editions over the years but was added to the New Canadian Library in 2003 (afterword by Robert Kroetsch), under series five, and was later re-issued under the fancier series six cover, which was the edition used in Canada Reads 2013. Fortunately, McGill-Queen’s University Press will be releasing a new quality re-issue in June 2018. Find a copy and add it to your bookshelf.

Laura Salverson – An Overlooked Pioneer of Canadian Literature

Throughout my almost two decades of collecting Canadian literature, I’ve created numerous spreadsheets to track my various goals: historically relevant series – like the New Canadian Library, certain authors, and important Canadian literary awards. The assemblage I am most proud of is my collection of English language Governor General’s Literary Award winners. Over the years, I have managed to round up all but one winner of the fiction prize, all the poetry and drama winners when the award was split in the early 80s, and many of the winners from the non-fiction, poetry or drama, translation, and both children’s categories. In total, my GG collection is 187 books. But I’ll have more on this collection in a later post. What I’m interested in today is the author of the one book I’ve sought after that has been the bane of my book collecting journey: Laura Goodman Salverson. Ms. Salverson is perhaps the most overlooked author in the early development, and perhaps the entire history, of Canadian literature.

Canadian literary awards. The assemblage I am most proud of is my collection of English language Governor General’s Literary Award winners. Over the years, I have managed to round up all but one winner of the fiction prize, all the poetry and drama winners when the award was split in the early 80s, and many of the winners from the non-fiction, poetry or drama, translation, and both children’s categories. In total, my GG collection is 187 books. But I’ll have more on this collection in a later post. What I’m interested in today is the author of the one book I’ve sought after that has been the bane of my book collecting journey: Laura Goodman Salverson. Ms. Salverson is perhaps the most overlooked author in the early development, and perhaps the entire history, of Canadian literature.

Laura Goodman was born in Winnipeg on December 9, 1890. Her parents were Icelandic immigrants, Lárus Guðmundsson and Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir. It has been recorded that throughout her youth, her parents explored western North America with their young daughter in tow; Laura did not even learn English until the age of ten. These explorations with her parents helped steep Laura in her family’s Icelandic heritage and the history of this ancient and proud culture. In 1913, Laura married George Salverson, a railwayman.

Laura Goodman was born in Winnipeg on December 9, 1890. Her parents were Icelandic immigrants, Lárus Guðmundsson and Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir. It has been recorded that throughout her youth, her parents explored western North America with their young daughter in tow; Laura did not even learn English until the age of ten. These explorations with her parents helped steep Laura in her family’s Icelandic heritage and the history of this ancient and proud culture. In 1913, Laura married George Salverson, a railwayman.

Laura Salverson’s writings were meant to supplement the family’s income. In the writing she produced in the first part of her career, she focused on the trials, adversities and drama of the early 20th century immigrant experience, particularly in Western Canada. She lamented the loss of culture of immigrant communities in the Canadian melting pot of the time and she was highly critical of the “American Dream.” Additionally, Salverson was a staunch pacifist and very outspoken against World War I.

So why is Laura Salverson such an important figure in Canadian literature that should never have been forgotten? Three reasons:

- In 1937 she won the Governor-General’s Award for Fiction for The Dark Weaver. Only the second year the award was given out, Salverson was the first woman to win the GG.

- In 1939 she won the Governor-General’s Award for Non-Fiction for Confessions of an Immigrant’s Daughter. The first woman to win in this category.

- Laura Salverson was the first person to win two Governor-General’s Awards and is still part of a very small group that has won GGs in multiple categories (a group that includes names like Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Atwood, Mordecai Richler, and Hugh MacLennan).

- Her first novel, The Viking Heart, was a longstanding title in the New Canadian Library (series number 116)

None of these books are still in print and they have not been in print for many years. The Viking Heart, the story of  1400 Icelandic immigrants to Manitoba and their experiences from 1876 to World War I, was taken out of print as of the third series of the New Canadian Library (late-1970s/early-1980s). The Dark Weaver, a pacifist novel about a group of Nordic immigrants to Canada who volunteer to fight for the British in WWI, seems to have only been published once in Canada, the original 1937 Ryerson Press edition, and once in Britain, the 1938 Sampson Low, Marston & Co. edition. Confessions of an Immigrant’s Daughter, Salverson’s autobiography which is a deeply personal record of the Nordic community’s conflict and assimilation within the English majority, was reprinted as recently as 1981 by University of Toronto Press as part of its Social History of Canada series.

1400 Icelandic immigrants to Manitoba and their experiences from 1876 to World War I, was taken out of print as of the third series of the New Canadian Library (late-1970s/early-1980s). The Dark Weaver, a pacifist novel about a group of Nordic immigrants to Canada who volunteer to fight for the British in WWI, seems to have only been published once in Canada, the original 1937 Ryerson Press edition, and once in Britain, the 1938 Sampson Low, Marston & Co. edition. Confessions of an Immigrant’s Daughter, Salverson’s autobiography which is a deeply personal record of the Nordic community’s conflict and assimilation within the English majority, was reprinted as recently as 1981 by University of Toronto Press as part of its Social History of Canada series.

Salverson’s early works can be read through a variety of lenses (her later works drifted towards traditional Nordic romances and adventures that got away from her earlier Canadian based books). She can be read to gather insight into the early 20th  century immigrant experience, anti-war sentiments around the time of WWI, Western Canadian settlement, and more generally, Salverson is a woman’s voice at a time when there were few women writers making waves. That is, I should add, these works can be read that way if you are able to get your hands on the text to read.

century immigrant experience, anti-war sentiments around the time of WWI, Western Canadian settlement, and more generally, Salverson is a woman’s voice at a time when there were few women writers making waves. That is, I should add, these works can be read that way if you are able to get your hands on the text to read.

The Viking Heart and Confessions of an Immigrant’s Daughter are still relatively easy to find on used book sites. Abebooks has 25 listings for Confessions ranging from $4.00 for an 80s reprint to $250.00 for a signed original copy and The Viking Heart has 15 listings ranging from $10 for a New Canadian Library edition to $80 for a signed first edition. The Dark Weaver though has gained a reputation of being the unicorn for CanLit collectors. This book is notoriously hard to find – there are no listings anywhere on the internet for a used copy and libraries will typically not lend it out due to its rarity and age of the volumes on hand. Even finding a photograph of the book is challenging. The Dark Weaver is the only GG Fiction winner I do not have on my bookshelf. Since Salverson died in 1970, her work is not in the public domain, so it is also not on any ebook sites like Project Gutenberg  Canada. The only available version of the text anywhere is on the Peel’s Prairie Provinces project page of the University of Alberta’s library website; the text available is a scanned image of each page of the 1937 edition. If you are hardcore enough, like me, you can go through and download the individual TIFF image file of all 416 pages (I believe this took me about three hours). So, you can read this book, but you must put some work in for it.

Canada. The only available version of the text anywhere is on the Peel’s Prairie Provinces project page of the University of Alberta’s library website; the text available is a scanned image of each page of the 1937 edition. If you are hardcore enough, like me, you can go through and download the individual TIFF image file of all 416 pages (I believe this took me about three hours). So, you can read this book, but you must put some work in for it.

Ultimately, I think Salverson is just one symptom of a greater problem in Canadian literature of important titles going out of print, but this is an article for another day. In three years, Salverson’s work will enter the public domain, so it is likely that availability will increase then. This, however, is a copout. I find the fact that some university press or academic publisher has not re-issued her most important works, in an edited ebook form at the very least, a great cultural shame. Salverson needs to take her place among the important Canadian writers of the 1930s and be held high with names like Stephen Leacock and Gwethalyn Graham.

References and Resources:

The Canadian Encyclopedia

Athabasca University Profile

Library and Archives Canada Profile

University of Alberta, Page scans of The Dark Weaver

Back in Business – New Perspectives and New Styles

When I first started this blog in June 2010 I had modest intentions. My primary goal was to simply have a creative outlet to lay down some thoughts on the Canadian literature I was consuming as I had no one in my immediate social circle that had the same taste in books as I did. The site grew steadily and after just a few months I had a solid library of posts. In early 2011, I started getting emails from publishers, including well known Canadian publishers like Brick Books and Goose Lane; I was also having regular conversations with writers directly via Twitter. These editors and writers were actually asking me to review their novels, story collections and books of poetry. I was even getting unsolicited books in the mail from some of these publishers. I was once quoted on Canada Reads to start a discussion and I was interviewed by The Toronto Star about the death of a well known book reviewer. Once the novelty of all this wore off, I found the whole idea burdensome and took a break from posting. In the ensuing years, I would sporadically return with a few reviews or articles and then disappear again for months at a time. I could never put my finger on it but I would always quickly lose my passion for managing this blog. Then in 2015, shortly after my son’s second birthday and a career move, I unceremoniously gave up on the blog and left it in limbo.

In mid-2017 my family moved to a new house; after unpacking and getting comfortable in a new position I recently took, I got back into the habit of nightly reading and I started thinking about this site more and more. I started to wonder why I kept taking regular breaks from posting… why do I keep starting up again… should I give this site to someone new who is more engaged…. I came back to the question of “why did I start this blog up in the first place?” Looking back at my 27-year-old self in mid-2010, I would say my main goal was to talk about Canadian books. Full stop. In exploring my thoughts on a particular book I could take so many angles – characters, writing, plot, themes, humour, social relevance, historical relevance. I could go full on academic and put that English degree to work – apply a critical lens such as a Marxist reading, analyze the work using Foucault’s ideas of panopticism, venture down the road of new-historicism and explore the sociological context of the piece. The pattern I fell into, especially once publishers and writers took notice of my blog, was treating my posts more like critical reviews than anything else.

Throughout my formal education in literature (a BA with an English major and half of a Master’s degree), I approached literature in a starkly different way from a lot of my peers. My overarching view of literature (and all acts of cultural creation) is that every work is the intersection of history, geography and psychology. With the guidance of a few of my favorite professors in my younger days, I also came to understand that each time we read something, we re-evaluate each of those intersections on multiple levels because of our own contemporary contextual biases. This is how I approach everything I read and ultimately, I feel this is how I need to approach my writing about books.

One thing is clear, I am not a book critic. Most book bloggers aren’t critics yet they pretend to be (perhaps they are addicted to the free review copies). I pulled away from playing the critic a little bit once I stopped taking review copies from publishers and authors, but I still struggled to find my voice in my posts. After thinking about this lately, I feel ready to revive The Canadian Book Review with a fresh new perspective and approach. I am not interested in doing critical reviews of books. I am interested in talking about books – what spoke to me, what did I like to not like, how this relates to contemporary life, some historical tidbits of the book or author I find interesting – all within my particular window of how I see literature.

So with that, I am happy to say that The Canadian Book Review is back in business. I hope this new iteration of my blog does not disappoint.

Skim by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki

Winner of the 2008 Ignatz Award for Outstanding Graphic Novel

Winner of the 2009 Doug Wright Award for Best Book

Shortlisted for the 2008 Governor General’s Award for Children’s Literature

I’ve talked on this blog before about how young adult lit isn’t really my thing, unless it is a particularly important or well-known piece. Also on this blog, I’ve also talked about how the graphic novel isn’t a genre I’m especially familiar with. In 2011, when a graphic novel, Essex County by Jeff Lemire, was chosen for Canada Reads, I wasn’t exactly thrilled. As I said then, I see graphic novels as not a literary form per se, more of a blend of art and literature – a genre in its own right without parallel. The number of graphic novels in my CanLit collection has grown slightly – I’m up to a whole 5 titles now. That number may grow though, I’m going to be starting to collect the winners of the Governor-General’s Award for Children’s Illustration in the near future now that I’ve gathered all of the fiction, poetry, and drama winners.

Skim fits my aforementioned criteria. It is a young adult graphic novel that is held in high regard in the literary community and was an interesting magnet for some controversy in 2008. No other GG category seems to stir up as much trouble as the Children’s Lit award does (although there was also a snafu in the poetry category this year). This book was nominated for the Governor General’s Award for Children’s Literature, but only one of the two “creators” were credited in the nomination – Mariko Tamaki; her cousin, Jillian Tamaki, the illustrator of the book, was omitted. There was an outcry in the comics community over the exclusion because of the collaborative approach taken with this genre (funny enough though, not a peep was made when Jillian herself won the illustration GG for This One Summer last year).

Mariko and Jillian Tamaki’s Skim, set in 1993, tells the story of Kimberly Cameron (aka Skim). She is a student at an all-girls high school and is a rather unremarkable average “goth” kid. She goes through the typical crucible of being a teenaged girl – sexuality, shifting friendships, social status, and growing up.

Nothing remarkable happens in this book. If you’ve been to high school, you’ve experienced a lot of what these girls and Skim go through. What is remarkable about this book though, is the way the authors are able to use their particular combination of art and text to build a connection with the title character to the point that you experience her world through her eyes.

The art, from beginning-to-end, is constantly shifting, mirroring the emotional somersaults that take place in the mind of a typical teenager. Jillian Tamaki doesn’t stick to one particular type of illustration – she seamlessly moves from comic strip panels, to full page artwork, to two-page spreads, and to every combination in between. She switches aspects, uses zooming to great effect (I have no other word for it), uses shadows and reflections in interesting ways, and Tamaki is excellent at capturing extremely complex emotion in a single framed facial expression.

In terms of the text, I was interested in the first-person perspective. The text is presented in three different ways – as Skim’s diary entries, her internal stream-of-consciousness, and dialogue. Despite being fairly text heavy compared to the few other literary graphic novels I’ve read, Mariko Tamaki is very efficient with her writing. More importantly though, Tamaki manages to really capture the idioms of teenaged girl without sacrificing the depth and thematic impact of Skim’s story.

So all-in-all, Skim was a very enjoyable read. The primary characters are well developed, the artwork is visually appealing and continually changing, the writing is of a very high quality, and the book deals with themes that will be present as long as teenagers continue to exist. Skim is clear evidence of why Mariko and Jillian Tamaki are powerful forces in the world of the Canadian graphic novel.

The Fly in Autumn by David Zieroth

Winner of the 2009 Governor General’s Award for Poetry

David Zieroth is a pretty typical Canadian career poet. He regularly puts out collections, he taught English at the post secondary level, and he adheres to a fairly traditional lyrical style. As a side note, a former English professor and thesis advisor of mine, Richard Lemm another typical Canadian career poet, is mentioned in the acknowledgements of this book. In 2009, this career poet published his masterpiece and was awarded the top prize in Canadian Poetry, the Governor General’s Award. The Fly in Autumn is a good example of a satisfying poetry collection accessible, tight in terms of metaphor and symbol, not afraid of humour, and the author doesn’t go out of his way to reinvent the wheel in regards to style.

Now, I have to be honest, this isn’t going to be the most insightful review ever written. I read this book one night in bed when I was very tired, not feeling well and half tripping out on cold and sinus medication.

The strength of this book is the absurdest twist Zieroth takes with a lot of his poems, particularly the closing, and title, sequence, “The Fly in Autumn.” Like in “Insurance”:

Insurance offices are full of fat men

(cramped behind small desks stacked

with forms and notes) willing to act

as agents while chewing on a time when

they were blessed with a full head of hair.

This one’s thinking of lunch, the eclair

As you can see from this stanza as well, Zieroth isn’t afraid to throw a rhyme into the mix here and there. The pattern above, ABBACC, or close enough, is the one which the author continually returns. Zieroth uses this scheme in about a third of the poems but manages to avoid the sing-song feeling that sometimes roars its head with rhyming in contemporary poetry.

I’ve ranted on this blog about how much I am annoyed by collections of poetry that try to find something sublime or transcendent in the minutiae of everyday existence. This book had the potential to go in that direction, but fortunately for all involved, Zieroth took simple subjects and treated them to a quirky re-imagining.

Glenn Gould by Mark Kingwell

The name Glenn Gould conjures images of greatness, madness, and everything in between. Gould was, without a doubt, one of the greatest classical musicians of his time, if not ever. But, he was also the poster boy of eccentricity. His Goldberg Variations, which bookended his career, are works of legend in the world of classical music, and, at the same time, he was a hopeless hypochondriac, mentally ill, and addicted to a cocktail of prescription and over-the-counter medication. If there was ever a textbook case of contradictions, Gould was it. I first became aware of Gould’s existence 13 years ago in a Canadian Literature class at St. Mary’s University, during a unit on Northern lit in which we listened to his esoteric radio “documentary” The Idea of North. I am a relative newcomer to his music though; I’ve only been regularly listening to him for about a year (the Google Play streaming service has a fairly comprehensive Gould catalogue). He is, not surprisingly, one of the subjects in the Extraordinary Canadians series from Penguin. Philosopher and professor Mark Kingwell takes up the challenge of examining this colourful character. In doing so, Kingwell pushes the boundaries of the biography genre, even interpretive biography, to the extreme.

Kingwell abandons the traditional narrative form that biographies, of any type, typically take. This book could be better described as philosophical biography that attempts to get at the core of what made Glenn Gould tick, rather that simply tell his story. Not all biographical details are left out though: Kingwell does examine some important moments and elements of his subject – including the beginning of his professional career, his love of the microphone and abandoning of live performances, his important recordings including the Variations, and his more unusual personal attributes.

Many of the philosophical digressions and their relation to Gould were quite interesting – even though philosophy is not a discipline I was particularly fond of as a student. Kingwell looks at different aspects related to the philosophy of music and art – such as the line between composer and performer, the idea of “genius” in relation to music, and notions of performance whether live or recorded among others. Importantly, and ultimately necessary in a general audience book, the author is able to delve into this concepts using non-academic language free from much of the jargon inherent in any discipline.

I always hope to learn something whenever I read a biography of someone with whom I’m already somewhat familiar. Kingwell delivered. In the author’s examination of Gould, he looked beyond just the music and undertook a detailed study of his expansive written works. I didn’t know that Gould was a somewhat prolific, if not idiosyncratic, essayist. Over the course of his career, he published numerous articles in piano magazines (and also recorded a handful of spoken word records). In reading this book, it is clear that these somewhat rambling and occasionally incomprehensible articles – which include interviewing himself and regularly referring to himself in the third person, offer the clearest glimpse into the mind of this mad genius.

Overall, I was satisfied once I finished this book. If you are looking for a lot of information and straight biographical facts about Glenn Gould, you’re going to have to look elsewhere. But, as I’ve said before, this is an excellent philosophical biography of Gould. Mark Kingwell does a great job of getting to the heart of the enigma that was Glenn Gould. And from a different angle, Glenn Gould offers interesting explorations of the nature of music and art in today’s society that would be of interest to anyone who takes music seriously. Another great entry in the Extraordinary Canadians series.

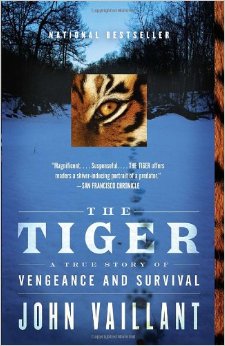

The Tiger by John Vaillant

Winner of the 2010 B.C. National Book Award for Non-Fiction

Winner of the 2010 Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Award

Winner of the 2010 CBA Libris Award for Non-Fiction

A Globe & Mail Best Book ~ 2010

A Quill & Quire Best Book ~ 2010

Selected for Canada Reads 2012

The 2012 edition of Canada Reads switched gears a bit and focused on non-fiction titles for the first time. I remember thinking then that The Tiger by John Vaillant stuck out a bit from the others. It was the only book that didn’t have a Canadian connection, other than the author’s nationality, and it was the only history narrative, while the other four were all memoirs. As such, this title got a rough ride on the show. But, more than most of the other titles that year, this one caught my interest. I planned on reading the book while listening to shows, and it only took me over 3 years to actually get to it. Who wouldn’t be interested in a classic man-versus-nature story of a man-eating tiger? There is a certain primitiveness to this idea. A challenge to Man’s rank in the natural pecking order. What Vaillant has delivered in The Tiger, is an interesting mix of history, nature writing, political science, and psychology.

I’m going to give The Tiger a solid “ok.” Certain aspects of the book were very interesting. Vaillant’s digressions into the biology, ecology, evolution and biogeography of tigers were the highlight of the book; additionally, he went into great depth in exploring the current conservation status and the sharp decline in tiger numbers. During these chapters, I felt strong overtones of one of my favorite nature titles, Song of the Dodo. Another strong point of this book was the correlations Vaillant drew between perestroika – the opening of the Soviet economy in the late 80s – and the desperate poverty in this remote region of Russia forcing people to resort to things like poaching. It was through this particular lens that the central players in the story were most interesting and developed.

This book was a bit of a slog though. The actual forward motion of the narrative component was a little slow and at some points came to grinding halt. The Tiger could have easily shed 50 to 75 pages. But, oddly enough, during the third and final section, “Trush”, the narrative took off with the pace that I was hoping for and, ultimately, you as the reader do feel satisfied with the conclusion.

With all of that being said, one thing that definitely stands out is the amount of primary research that the author must have done to complete this book. Other than one documentary film and the contemporaneous news stories, there would be very little available in terms of first-hand accounts of these incidents. For the author, I imagine striking out into the backwoods of isolated eastern Russia must have been like entering a different planet.

That’s all I’ve got. This is a rather short review, but I just don’t have much to say. I find I always have lots to say on books that I either really liked or really didn’t like, but books like The Tiger where I am just kinda “meh, it’s alright,” just don’t elicit enough excitement in me either way to write a lengthy response.

Dance on the Earth by Margaret Laurence

I’ve said before on this blog that Margaret Laurence is my number 1 favorite author. It is because of her I fell in love with Canadian Literature and reading in general. Laurence died relatively young and had very little output after her magnum-opus, The Diviners, was published. Over the years, I kept a few of Laurence’s works on reserve for future reading because I don’t like the finality of reading everything she has published. He last book, and only major work after The Diviners, is her posthumously published 1989 memoir Dance on the Earth. Laurence died in 1987, shortly after completing a semi-final draft and before publication. In the foreword, her daughter Jocelyn does an excellent job of describing the last few months of Laurence’s life and the rush and struggle to finish this book. Her cause of death wasn’t actually revealed until James King’s biography was published many years later. There is no particular reason why I decided to read this now, I just felt that it was time. Dance on the Earth was an excellent coda on the writing career of a masterful author. In fact, this strong woman being ripped from this world while writing her memoirs could even be described as Laurence-esque.

Laurence crafts an autobiography that is all her own. She doesn’t follow a standard A-to-B-to-C structure. Instead, she frames each of the four primary chapters in terms of the important mothers in her life: her biological mother, her step-mother, her mother-in-law, and finally herself. Within each of these frames, Laurence discusses the major events, important people, and central places that made her who she was and helped shape her pacifist and feminist views. Interestingly, she doesn’t really get into discussing her own writing until the chapter where she focuses on herself. Laurence gets into her state-of-mind with her works, her reactions of reviewers, her dislike of the publicity/business end of it, and why The Diviners was her last major work. This section more than the rest is really a fascinating glimpse into a brilliant creative mind. Additionally, the memoir is peppered with wonderful letters between Laurence and others, with the letters to Adele Wiseman being a definite highlight.

The main bulk of the book is written with the same understated powerful prose that punctuated her Manawaka cycle, except Laurence herself takes the place of Hagar, Rachael, Stacey, Vanessa, and Morag. She is very open, vulnerable, and pulls no punches. My one negative critique of the book is some of the items included in the “Afterwords” section. The previously published essays, including articles on nuclear disarmament, feminism, and a convocation address were fantastic, they were wonderfully written, articulate, and quite persuasive in their arguments. But, the poems that were included were not that great. It upsets me a little bit that the final work of Laurence’s career is concluded with a bit of mediocre poetry that seems to have been written for personal occasions, not publication. I’m sure this was an editorial decision made after Laurence had left us.

It’s clear that Margaret Laurence knew her life was coming to an end (as we now know she made the decision herself on when it would end). This was also clear in the way the memoir ended. She seemed to wrap things up quickly and almost suddenly because she knew that’s how it had to be. This is not a criticism of the book or even something that takes away from it. Instead it further punctuates that the fact that this great author had a lot more to give to our country, even if her prime writing days were behind her.

The Door is Open by Bart Campbell

Finalist for the 2002 Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize

Finalist for the 2002 City of Vancouver Book Prize

Golf season is winding down so I guess it’s time to start reviewing some books again. I recently moved my bookshelves around and I wanted to read a book from the top shelf of the first case, which happens to be my paperback non-fiction shelf. The book that caught my eye was Bart Campbell’s The Door is Open: Memoir of a Soup Kitchen Volunteer.

This memoir tells the story of a hospital lab technician who volunteers at a drop in centre in Vancouver’s East Hastings area after he and his wife separate. Across Canada, East Hastings has the reputation of being a very poor, hard, and drug and crime infested area. Images are conjured up of prostitutes, heroin, and destitution. This memoir was published in 2001 so it was before the opening of the safe-injection site InSite, and other focused government efforts, started to make a very small dent in the visible poverty.

This book is very short, with the epilogue it clocks in at only 144 pages, but it is 144 very well used pages. Each of the 10 short chapters pack a very strong punch. The Door is Open is more than simply a memoir filled with anecdotes about the characters he came across while volunteering, of which there are lots; Campbell looks at the nature of poverty and all of the complications that go along with it. In methodical fashion, he explores concepts of poverty and homelessness, crime, addiction, prostitution, mental health and suicide, and survival. Campbell beautifully pieces together cold-hard facts, personal observations, anecdotes, and expert opinions to paint a brutally honest portrait of East Hastings, which is, as he points out, the “poorest forward sortation area of all 7,000 postal prefixes” in Canada.

At the end of each chapter, Campbell has a coda of sorts with excepts from diaries he kept while volunteering. These excerpts act as real human examples of the themes he explored in the preceding pages. Also peppered throughout the book are beautiful black and white photographs of the East Hastings landscape.

I’ve been fortunate in my life that I’ve never had to stare down the prospect of real poverty. When I was younger I was the stereotypical “poor student,” but this was far from being “poor.” It just meant I had to call my parents to borrow a few bucks. I always had a job, a roof over my head, cable TV and internet, food, a car, and a few books to read. Poverty and desperation on this level is something middle-class Canadians like myself just don’t have to think about, even though, as Campbell mentions, Statistics Canada points out that most Canadians are only a few months away from homelessness. The Door is Open is a hard read because it forces you to face this world. The author pulls no punches and maybe, just maybe, he might change a few minds on the homeless.

Canada is in the midst of a federal election and we recently had a provincial election here in PEI. As I finished this book last night, it actually got me thinking (which was likely a goal Bart Campbell had), about the political approaches that are the typical go-to’s in this country. Over the last few years, it’s been all “affordable housing.” Just last week Liberal leader Justin Trudeau promised tax credits to developers to build low income housing. If Trudeau came to my door step right now, I would hand him a copy of this book, and ask him how this would help the people Campbell writes about (answer is, it wouldn’t).

The Door is Open was on the longlist for Canada Reads this year; I hadn’t actually heard of the book prior to this. Even though it is almost 15 years old at this point, it is still, quite sadly, very relevant. In a country with an economy worth over $2,000,000,000,000, there is no need for people to have such a meager existence. This is a fantastic book and a must read